Loving Our Refugee Neighbors

- Laurie Kagay

- Sep 28, 2018

- 5 min read

Uganda is ‘home’ to 1.4 million refugees, the highest number in its history. Uganda hosts more refugees than any other country in Africa, and is one of the top five refugee-hosting countries in the world. Refugees in Uganda come from the surrounding countries of South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Burundi, among others. Uganda’s refugee policies are among the world’s most progressive, which, along with the country’s relative peace, makes it a (somewhat) welcoming destination for people fleeing their country.

Tennessee is ‘home’ to over 57,000 refugees (less than 1% of the state’s population), with over half living in Davidson county (Nashville and its suburbs). The number of refugees in Tennessee has more than doubled in the last 25 years, with over 2,000 accepted in 2015 (30 percent more than in 2014), and over 1,500 accepted in 2016. Refugees come from Bhutan, Burma, Iraq, Somalia, Cuba, Eritrea, Sudan and Kurdistan, among others. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Less than one percent of all displaced persons <65.3 million people worldwide> are settled to another country, and the United States takes about one-tenth of that one percent. Refugee vetting takes from one-and-a-half to three years, and the average wait time in a camp is about 10 years.”

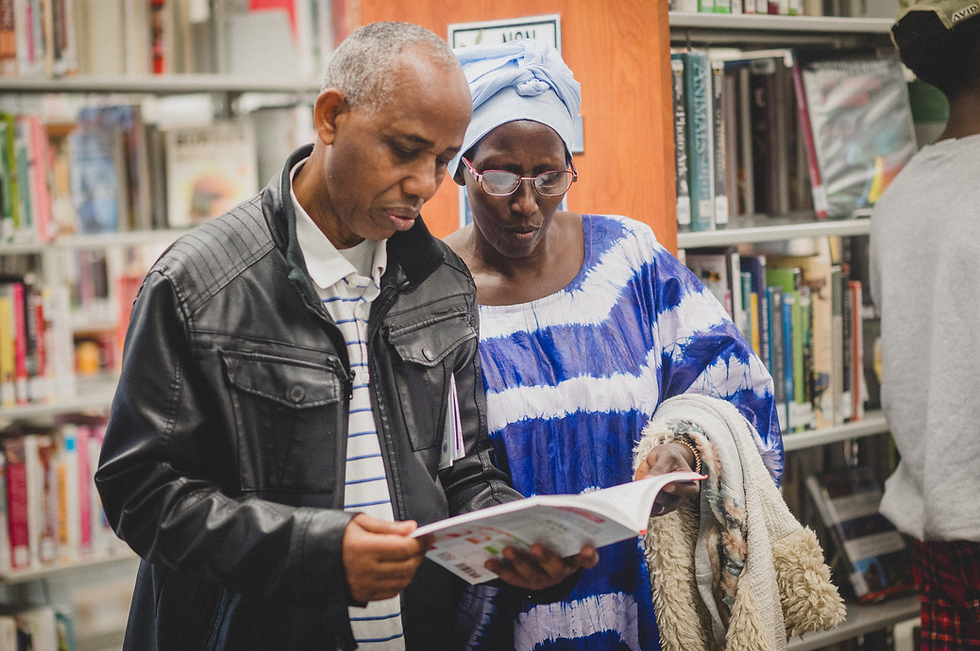

Joseph (left) is a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and pastors a congregation of Congolese refugees in Nashville. Before moving to the US, they were refugees in Uganda for years, having had to flee conflict in the Congo. Many of them are very new here, and some are still arriving. Nyago met Joseph and his congregation in June and has begun forming relationships with them.

John Nyago, one of G.O.D.’s East Africa managers and a community networker for G.O.D.’s Refugee and Immigrant Care Program, grew up and lived in central Uganda for 25 years before relocating to Nashville. Consequently, he is well acquainted with the refugee population, their plight as displaced people and their needs as human beings.

I got the opportunity to sit down with Nyago and talk about refugee populations in Uganda and Nashville, his own experience with refugees, and the responsibility he takes (very seriously) for the well-being of those in his midst who’ve been displaced.

According to Nyago, the general perception of native Ugandans toward refugees in Uganda is positive (not so in America, where only 51 percent of Americans even believe we should welcome them here). Ugandans are sympathetic to refugees because their tragic circumstances are in part their own history. Internal instability, political conflict and civil wars in nearly every region of Uganda over the past 20 years have displaced Ugandans throughout the country.

Nyago attended secondary school with refugees coming from camps in northern Uganda boarded at his school. He remembers how humble they were, how differently they carried themselves than children with families. He says they would “get lost in their minds and look to be so far away, thinking about their families and not knowing if they were alive or dead. Young people—all under 20–dealing with situations they didn’t know how to process.”

Nyago (right) pictured at Bombo Senior Secondary school in 1998 where he attended high school with Grace (not pictured).

Conversations Nyago had with refugee classmates as a teenager have remained with him. He told me the story of one classmate in particular, Grace. It was Parent Visitation Day and the students were excited and rushing to see their families as they arrived. However, Grace wasn’t. Nyago asked her if anyone was coming for her. She said no. It took a lot of prodding, but she finally opened up to him. Due to rebel activity in her village, her parents and siblings were leaving their house every evening for months to sleep in the bush. One night rebels found them in the bush and abducted them. They were forced to walk all night until it was too dark and they were too tired. She had been praying to God the whole walk that she would be saved and not die. They reached a spot where they joined other rebels and abductees. They were all circled and told to rest. She laid down to sleep, praying the whole time, and at some point in the night God woke her up and told her to run. She got up and started jumping over people and then running. She heard the soldiers waking up, but they thought it was an animal, so she kept running. She ran until she reached a place where she was taken in by nuns, who cared for her and had brought her to the school. She hadn’t hear from her family since that night. Nyago says her story was common, much too common. He still prays for Grace, that she’s alive and well.

Today, Nyago volunteers as a community networker between the G.O.D. community and refugee groups in Nashville. His work in aiding them is anything but cookie-cutter, as he strongly believes in the need to offer individualized care. He says, “If we are going to effectively serve refugees, we need to know them as human beings, each of them unique, responding differently to the traumatic events in their lives as they express various needs even beyond the practical ones.”

Nyago (bottom left) attends a fellowship of Kenyan believers immigrated to Nashville. They gather in various members’ homes and share a potluck meal together before studying the Bible. The man in the center is a retired reverend who lives here with his wife (far right) and children.

In his experience, refugees often struggle with blaming themselves and others they had trusted for the situations they and their families are in, and asking themselves where God is, if he’s even there, and why they would go through such things if so. Wounds like this make life very stressful, especially when left unaddressed (as they often are) while trying to survive in an unfamiliar world. Nyago helps facilitate the kindness and hospitality through service necessary to help them reconsider these perceptions of themselves, others and God. As he and other partners have demonstrated genuine concern for their well-being and provided real care, he’s seen trust and confidence being rebuilt in refugees. In this way, he says, “I get to help redeem the image of God that gets tainted and ruined by a world of wrongdoing. I get to fulfill the law of God, which says, ‘When an alien resides with you in your land, you shall not oppress the alien. The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God’ (Lev 19:33-34). Though the world sets a lower standard, I go by God’s. Our efforts have to be marked by awareness and sensitivity, helping them feel loved and human again. They’re so vulnerable, and we must dignify them.”

Nyago also carries Micah 6:8 in his heart as he loves his refugee neighbor. “He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” Profoundly he says, “In order to walk humbly with God, you have to walk with those who are humble, with those who need justice, with those who know no kindness.” Some of the refugees Nyago works with currently are from the DRC, who were refugees in his home-country of Uganda before being relocated to the US. This is not their first time being neighbors. Nyago actively prays for the weights of trauma, guilt, mistrust and hate to be lifted as they encounter God’s people treating them as the valuable human beings they are.

Comments